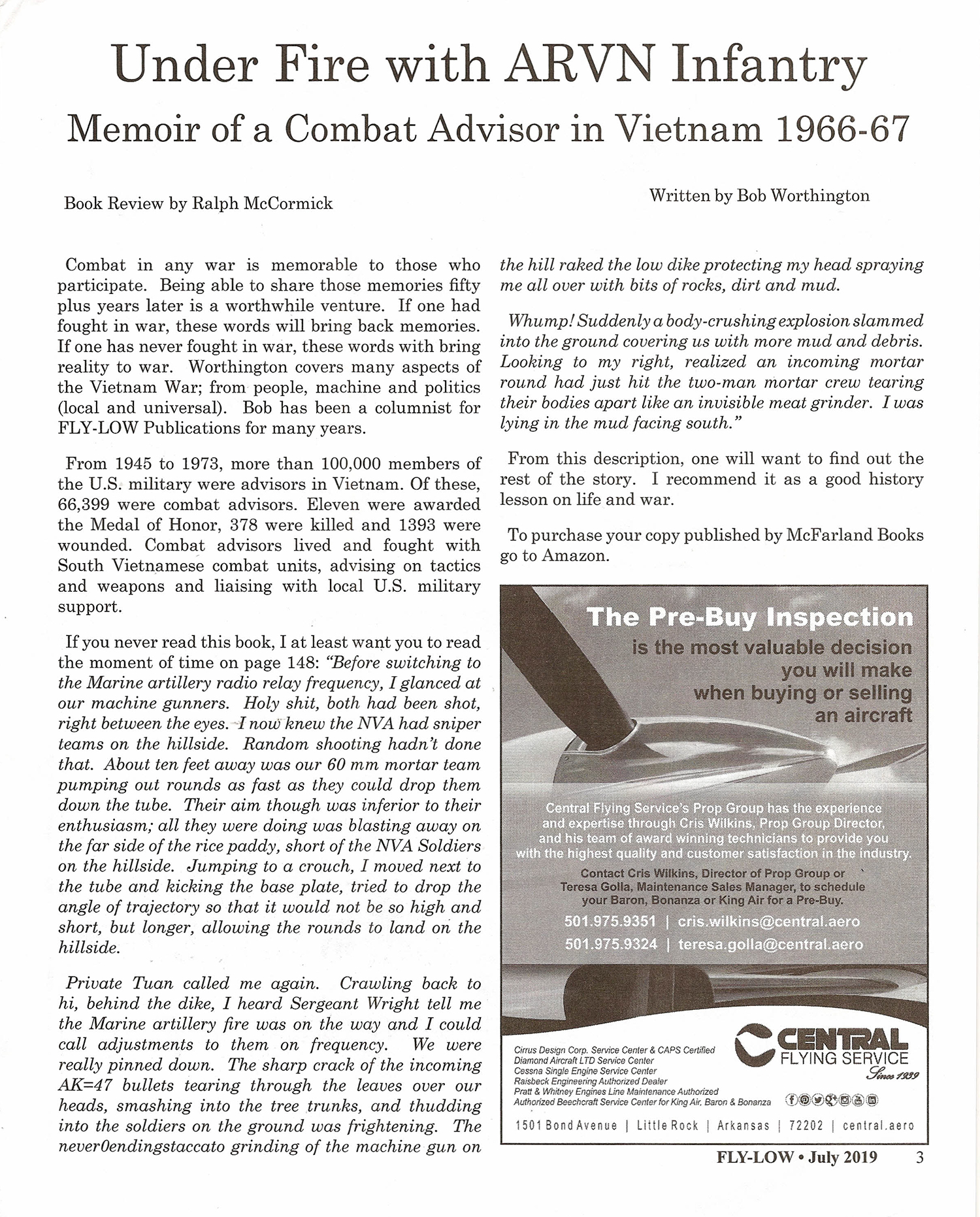

Book #3 - The Making of an Army Psychologist

In the early 1970s the U.S. Army was undergoing seismic changes. The Vietnam War had ended, almost 600 American POWs were released by North Vietnam, the draft was terminated and the Army itself was in dismal shape. A decorated former infantryman turned behavioral scientist, Bob Worthington returned to active duty as a clinician and served as a senior psychology consultant, helping the Army remain an effective fighting force. His insightful memoir describes his pioneering research in PTSD, the managing of a clinical service and mental health center, his work focusing on pilots and aviators, and a stint as a sports psychologist for the U.S. Olympics.

In the early 1970s the US Army knew the War in Vietnam was going to end and with it the draft. A non-conscript Army meant that all soldiers had to be volunteers and, to attract young people to join, the NCOs and officers had to be nice. But doing this could be difficult for older NCOs and officers. Thus, the Army thought that bringing former combat arms officers, who now had doctoral degrees in the behavioral sciences (psychology, counseling, social work), back on active duty, they could ease the transition from a compulsory military service to an all-volunteer force. The Army sought former combat officers in doctoral programs to return to active duty while getting their degrees. I was one of those.

In the last semester of my master’s program in counseling and psychology, I applied to a dozen psychology PhD programs, and every one turned me down. One said I had spent too long in the military and couldn’t think; another said my undergrad grades were too low (even though that was 10 years ago and my C+ average was from an Ivy League college); another said I had never worked as a psychologist nor published any research articles; and the reasons went on. Not one school wanted me. So, I graduated, got certified as an assistant school psychologist and a school psychometrist and worked as a counselor where I got my degree.

During that year as a psychologist I continued taking grad courses and now had experience working in the field. Toward the end of my first year, working, I again applied to PhD programs, all over again. But, now I was a different animal, I was a real live, certified, accomplished school psychologist. Also, I had taken the Miller Analogies Test and received a score in the mid-90s percentile. With my work as a psychologist, my state psychology certifications and my MAT score, every school accepted me the second time around. I took a perverse pleasure in telling most schools that after a closer look at their PhD program, I had decided it wasn’t good enough for me. I did accept the offer at the University of Utah PhD program in Counseling Psychology. And after a rocky start, I completed the program (and my American Psychology Association clinical internship as well as my dissertation) in two years with an A average.

While I reapplied to the PhD programs, I also applied to return to active duty as a psychology PhD candidate. Early in the spring of 1971, I was accepted into the PhD program at Utah (to start that fall) and that summer was brought back on active duty, as an Army Medical Service Corps major, serving as a PhD student.

My PhD dissertation was a comprehensive look at the post-service adjustment of Vietnam veterans. My research revealed that those soldiers who encountered problems after their service, also encountered problems in the Army. These same men entered the Army with problems (dysfunctional families, school dropouts, alcohol and drug addictions, job instability, and personality disorders), and left with the same problems.

Upon graduation, I was assigned to the Psychology Service at William Beaumont Army Medical Center at El Paso, TX, for a one-year post-doctoral fellowship in Community Psychology. The next year I was assigned to the Army Hospital at Ft Polk, LA as the only clinical psychologist on the entire post. At that time Polk was an Infantry Basic Combat Training base, so I was delighted to return to the Infantry, but this time as a clinical psychologist.

I had learned that Army hospitals had a budget to finance medical research projects. My behavioral science projects could be accomplished without extra funding, so my request for research funds was only to cover the cost of traveling to conferences to present my research findings. Virtually every research project presented for a conference was accepted so I did a lot of traveling. To get to most conferences, I would fly commercial air, usually taking a lot of time from Ft Polk. Pilot friends of mine suggested I become a pilot and fly myself. I did just that and thereafter, always flew myself (and my wife).

A major Army research project at Ft Polk was to test the concept of combining basic training with advanced individual training. That is, how much time and money could be saved by taking two separate eight-week training programs (and the week or two between for travel and re-orientation) to combine them into a single 12-week program? I was the psychologist examining cohesiveness and bonding related to the soldiers undergoing the training. Other researchers examined the effectiveness of combined training. We determined it could be done, cheaper and with more positive outcomes. It was presented to Army generals and the Army presented it to Congress. Senators from states which stood to lose Army training posts voted it down.

I also continued to research the adjustment of Vietnam era veterans and which soldiers made it through basic training and which ones did not. The findings were the same as my research with Vietnam veterans.

Nine months after arriving at Ft Polk, I was transferred to a new position at the Health Services Command in San Antonio, TX. This two-star command was responsible for all Army medical facilities and personnel across the US. My job, as the staff Psychology Consultant, was to stay abreast of every issue or concern regarding army psychology, be it health care, research, personnel, treatment, or education. I traveled two to four times a month to visit Army psychologists across the nation to follow what they were doing, provide seminars and workshops, or work on research programs.

During the next six years I became involved in numerous major research programs, as well as continuing a clinical practice at Brooke Army Medical Center, also at San Antonio. These included the DOD five year medical and psychological evaluations of all Americans held as POWs in Vietnam. I did all the Army psych evals for the last few years. I was also a member of the DOD Center for POW studies. It conducted research and published numerous papers and books. Another major project was for the US Olympics. The Army hosted and maintained the Olympic Modern Pentathlon Team, so the Army agreed to undertake a project to identify traits or characteristics of world class Pentathlon athletes and then evaluate young athletes to determine if they had world class potential. Most Pentathlon athletes were selected from high school and college running and swimming sports. Once they joined the team, they were taught horse riding, fencing, and pistol shooting. Our research showed there were no traits that could predetermine premiere athletes, but because I was a competitive long-distance runner (in my 40s) and as a former full-time professional athlete (pistol shooting), I became the sports psychologist for the US Olympics Modern Pentathlon Team.

I also became a forensic psychologist and worked with legal teams either defending or prosecuting military members. I would do psychological evaluations of the soldiers and then teach the attorneys how to properly present the evaluation information at the trial.

I continued to see clients and patients as a clinician and encountered several very unusual patients such as the psychotic lady, admitted to the psychiatric ward, because she drank too much coffee or the sergeant with a back injury who complained about his unprofessional treatment by a neurologist. No one paid attention to his complaint until he threatened to hold a press conference. He told the medical center commanding general he was a millionaire and as a sergeant he was being treated unfairly. The general thought the “millionaire” sergeant to be delusional and called me at home at 7 am, asking me to evaluate the NCO. I did and learned his complaint was true and he was a millionaire (during his tours in Vietnam, all his money was invested in rural property just outside San Antonio). Fifteen years later the land was now inside the city limits, making him a millionaire.

My wife and I started a management consulting company (she was president) which was doing very well. But working with businesses, I did not have a background nor education in business, which I needed. So, my wife and I returned to graduate school (separate schools) where we both received master’s degrees in business administration.

By 1981 I had accumulated 20 years of active duty and almost five additional years of active reserve service. My service had been Marines and Army, enlisted, NCO, and officer. My wife and I decided we had served enough (in this time I had three combat tours, also) so I opted to retire. This initiated another, different phase of my life. At this point, when I retired, I left psychology and began a new career as a business professor at a university.

Book #2 - Fighting Viet Cong in the Rung Sat: Memoir of a combat advisor in Vietnam, 1968-1969.

In February 1967, after my first tour in Vietnam as a combat advisor, I was a student in the Armor Officer’s Career Course. The Infantry branch decided I was to be cross-trained in Armor warfare. Upon graduation, I had orders for Ft. Benning, GA as an assistant editor for Infantry magazine, probably because of my Ivy League degree. Being a gung-ho infantry captain, though, I pressed for what was supposed to be the best job for an infantry officer, company commander; which I received.

I was proud to be honored by my commanders for the hard work and sacrifices as a combat advisor, to stay at Vann’s home and to be transferred to Saigon as a reward for faithful service. Shortly after arriving in Saigon and starting my new job, I learned the truth. I was not being honored for my hard work as a combat advisor but fired because I had displeased two generals in the U.S. Army 25th Infantry Division. What I had done as an advisor regarding refugee resettlement and security issues for rural Vietnamese farmers happened to be in opposition to the combat operations of the 25th Division.

One example was the 25th Division “Rome Plow” strategy. This tactic involved the use of a special two-ton plow blade (made in Rome, GA), which was designed to clear jungle growth from ground level up. The division would use Rome Plows to clear a 100-yard swath on either side of a major road, used as a main supply route, thus denying the Viet Cong the ability to hide and conduct ambushes, from the jungle.

Unfortunately, the Vietnamese pacification program involved removing Vietnamese peasants and farmers from their villages in the jungles, relocating them to newly built refugee sites alongside major roads as being better suited for security purposes. Thus, the Vietnamese would move its rural citizens to new locations, along major roads and then American units with Rome Plows would destroy refugee camps, rice fields, and anything else next to roads used as supply routes.

I was assigned to support Vietnamese government policies and operations and if they differed with American plans, I sided with the Vietnamese. So the 25th arranged to have me fired and replaced by one of their majors.

In Saigon my commander was a unique individual. He was a U.S. Army full colonel, James A Herbert, promotable to brigadier general. While an active duty officer, he was serving as a State Department Reserve Foreign Service officer. While working for him, I did not know that he was a founder of the Ranger Department at Ft. Benning, one of the Army’s first airborne rangers and a key player for Army special operations. During Korea, he commanded a Ranger company and was decorated for his actions defending terrain vital to a division operation, despite being severely wounded. I remained a friend of the general, even after leaving the Army. With the two commando companies in the Rung Sat, we conducted numerous raids on identified Viet Cong positions and destroyed the VC strong hold on the shipping canals leading into Saigon.

Many of our combat raids were special operation missions, based on acquisition of intelligence gathered by our Phoenix Program personnel. The Phoenix Program was a combined effort by both U.S. and Vietnamese military, Vietnamese National Police, our CIA, and Vietnamese government officials, down to the village levels. The goal was to identify and capture Viet Cong leaders and members.

Toward the end of my tour in Vietnam, I trained a U.S. Marine advisory team to replace me and my team members as advisors to the two commando units. I was diagnosed with Yellow Jaundice just prior to departing Vietnam, which was successfully treated after my return to the states.

I returned to Ft. Benning, where my family remained, and processed out of the Army. I left active duty but remained active in the Army Reserves. My family and I moved to Flagstaff, AZ where I entered a Counseling-Psychology Master’s degree program at Northern Arizona University in the fall of 1969. I received my degree in a year, worked as a counselor at the university for a year, and then moved to Salt Lake City to enter the PhD program in Counseling Psychology at the University of Utah. At the same time, the Army brought me back on active duty as a PhD student to then serve as an Army clinical psychologist. But that is an altogether different story, to be told at another time.

I needed money, so, newly promoted to major, I volunteered for another tour in Vietnam, as a combat advisor. Being in a Vietnamese combat unit and spending most of the time on combat operations meant I wouldn’t spend much money. If my family lived frugally, we would have enough saved at the end of my tour to afford grad school.

My second tour was mostly with Regional Force units (like our Reserve units), where I was assigned from MACV (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) to CORDS (Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support). CORDS was a single command made of U.S. military, the State Department, the CIA, and various other U.S. agencies. Its purpose was to combine military tactics with Vietnamese government programs to pacify rural areas and to support Vietnamese efforts at identifying and destroying the Viet Cong infrastructure. Both civilian (State Dept) and military advisors were assigned at District levels to advise on government and military operations (Vietnam had 250 districts, comparable to a county in the U.S.). I was a district senior advisor, twice, and my counterparts, the Vietnamese district chiefs, were always Vietnamese military officers.

My first district advisor position was on the Cambodian border (where the fighting was fierce, and the annual casualty rate was 500%, and I became one of the casualties). Next, I became the Senior Tactical Advisor to all the Vietnamese infantry units responsible for the security of all the bridges in Saigon. My last assignment was extremely interesting and very rewarding. I became the senior combat advisor to two Regional Force light infantry companies to train them as commando units. Our mission was to go after all the Viet Cong units attacking and disabling sea-going ships bringing goods into South Vietnam through the Saigon River and swamps of the Rung Sat Special Zone.

The Vietnamese troops were outstanding and very brave. The Viet Cong units had controlled the area for so long with no opposition, they became complacent, and rather easy to fight, compared to my time on the Cambodian border. When I began, I was transferred from Army control to the U.S. Navy Advisory Command as they were the advisors to all Vietnamese forces in the area because it involved the security of ships. I worked for Admiral Zumwalt and our success in combat resulted in me receiving two U.S. Navy decorations for Valor and two Vietnamese decorations for Valor.

My second tour in Vietnam was varied, exciting, interesting and very dangerous. It involved me being med-evaced after a combat operation due to a perceived cardiac arrest, ending up in the morgue, dead (I had hookworm, which presented signs of cardiac failure). I was shot up during a night special ops mission to interdict rockets coming across the Cambodian border to attack Saigon. I was told I was being transferred to an advisory assignment in Saigon because of my bout with hookworm and recovering from being shot, and as a reward for doing an extraordinary job as a combat advisor. I was even the special guest in the Vietnamese home of John Paul Vann, Deputy for CORDS for III Corps, who was the senior American I worked for.

Vann, a retired U.S. Army infantry Lieutenant colonel, believed in small unit tactics and patrols. He wanted the Vietnamese military squads and platoons constantly conducting night patrols. To ensure this was being done properly, he required his military district advisors (typically US Army majors) to persuade the Vietnamese to conduct these patrols and for the senior district advisors to accompany the squad and platoon patrols to make sure they did conduct a combat patrol instead of just moving out, into the brush and going to sleep. As a major, I went on more small-unit patrols than I ever did as a captain.

I was proud to be honored by my commanders for the hard work and sacrifices as a combat advisor, to stay at Vann’s home and to be transferred to Saigon as a reward for faithful service. Shortly after arriving in Saigon and starting my new job, I learned the truth. I was not being honored for my hard work as a combat advisor but fired because I had displeased two generals in the U.S. Army 25th Infantry Division. What I had done as an advisor regarding refugee resettlement and security issues for rural Vietnamese farmers happened to be in opposition to the combat operations of the 25th Division.

One example was the 25th Division “Rome Plow” strategy. This tactic involved the use of a special two-ton plow blade (made in Rome, GA), which was designed to clear jungle growth from ground level up. The division would use Rome Plows to clear a 100-yard swath on either side of a major road, used as a main supply route, thus denying the Viet Cong the ability to hide and conduct ambushes, from the jungle.

Unfortunately, the Vietnamese pacification program involved removing Vietnamese peasants and farmers from their villages in the jungles, relocating them to newly built refugee sites alongside major roads as being better suited for security purposes. Thus, the Vietnamese would move its rural citizens to new locations, along major roads and then American units with Rome Plows would destroy refugee camps, rice fields, and anything else next to roads used as supply routes.

I was assigned to support Vietnamese government policies and operations and if they differed with American plans, I sided with the Vietnamese. So the 25th arranged to have me fired and replaced by one of their majors.

In Saigon my commander was a unique individual. He was a U.S. Army full colonel, James A Herbert, promotable to brigadier general. While an active duty officer, he was serving as a State Department Reserve Foreign Service officer. While working for him, I did not know that he was a founder of the Ranger Department at Ft. Benning, one of the Army’s first airborne rangers and a key player for Army special operations. During Korea, he commanded a Ranger company and was decorated for his actions defending terrain vital to a division operation, despite being severely wounded. I remained a friend of the general, even after leaving the Army. With the two commando companies in the Rung Sat, we conducted numerous raids on identified Viet Cong positions and destroyed the VC strong hold on the shipping canals leading into Saigon.

Many of our combat raids were special operation missions, based on acquisition of intelligence gathered by our Phoenix Program personnel. The Phoenix Program was a combined effort by both U.S. and Vietnamese military, Vietnamese National Police, our CIA, and Vietnamese government officials, down to the village levels. The goal was to identify and capture Viet Cong leaders and members.

Toward the end of my tour in Vietnam, I trained a U.S. Marine advisory team to replace me and my team members as advisors to the two commando units. I was diagnosed with Yellow Jaundice just prior to departing Vietnam, which was successfully treated after my return to the states.

I returned to Ft. Benning, where my family remained, and processed out of the Army. I left active duty but remained active in the Army Reserves. My family and I moved to Flagstaff, AZ where I entered a Counseling-Psychology Master’s degree program at Northern Arizona University in the fall of 1969. I received my degree in a year, worked as a counselor at the university for a year, and then moved to Salt Lake City to enter the PhD program in Counseling Psychology at the University of Utah. At the same time, the Army brought me back on active duty as a PhD student to then serve as an Army clinical psychologist. But that is an altogether different story, to be told at another time.

From 1945 to 1973, more than 100,000 members of the U.S. military were advisors in Vietnam. Of these, 66,399 were combat advisors. Eleven were awarded the Medal of Honor, 378 were killed and 1393 were wounded. Combat advisors lived and fought with South Vietnamese combat units, advising on tactics and weapons and leasing with local U.S. military support.

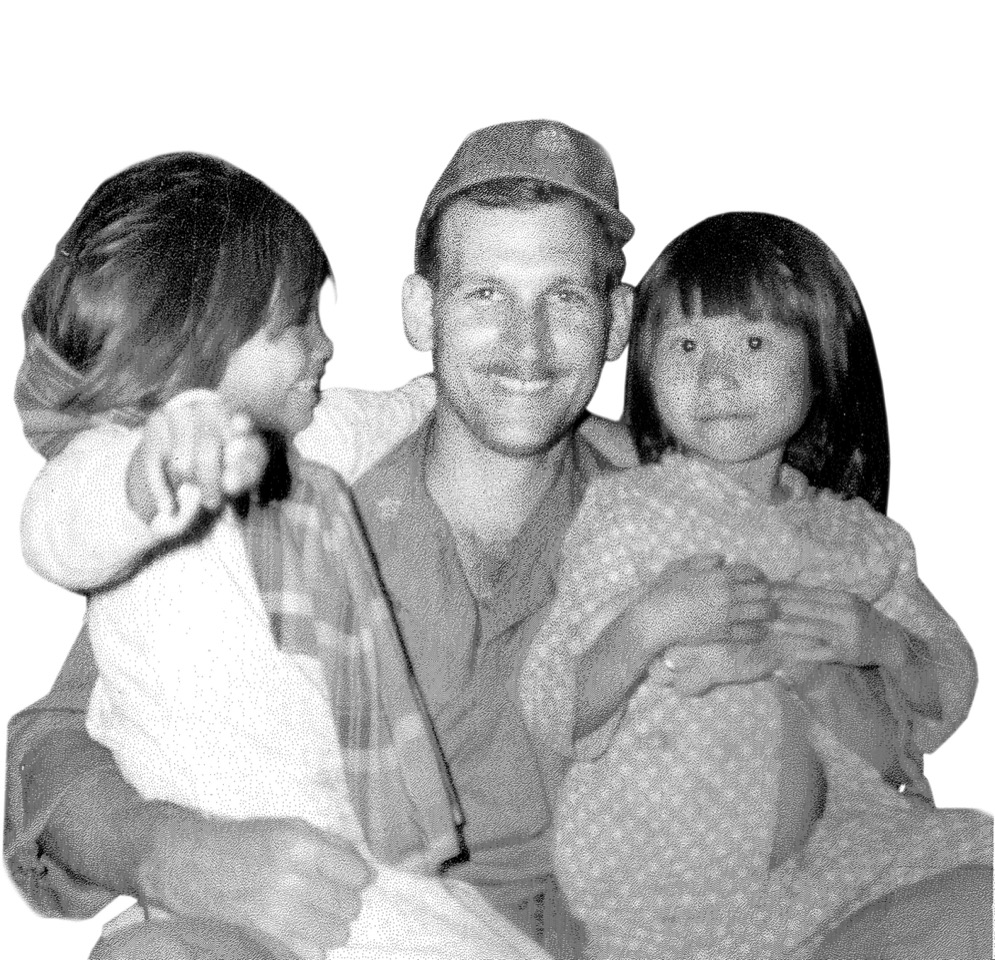

Bob Worthington’s first tour (1966 -1967) began with training at the Army Special Warfare School in unconventional warfare, Vietnamese culture and customs, advisor responsibilities and Vietnamese language. Once in-country, he acted as a senior advisor to infantry defense forces and then an infantry mobile rapid reaction force.

Worthington worked alongside ARVN forces, staging operations against Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army units, and coordinated actions with the U.S. Marines. He describes a night helicopter assault by a 320-man ARVN battalion against a 1,200-man NVA regiment. On another night, the Vietcong ceased fire while Worthington arranged a Marine helicopter to medevac a wounded baby.

Read the Reviews